Does CAPIT Teach Letter Names?

By Eyal Rav-Noy

© 2016, Capit Learning

The Importance of Letter Names

Letter names are important, but knowledge of letter names does not help students read or spell.

Students must learn letter names, and teachers must teach them for many reasons. For example:

Without letter names, how would one ask a spelling question such as: "Kari, how do you spell your name? Is it with the letter K or the letter C?"

To efficiently look up words in a dictionary, one must know the names of all the letters and their correct order (i.e., a, b, c)

In our professional development sessions, we urge teachers to teach letter names. Fortunately, teaching letter names is easy. Any child who watches a few Sesame Street episodes quickly learns the names and order of the alphabet letters.

A Phoneme-First Approach

We made the conscious decision to avoid letter names in our phonics curriculum because knowledge of letter names is unnecessary for reading and spelling. Again, letter names are important, but this knowledge does not help students learn to read or spell.

One might ask the following: “What's the harm in teaching letter names to beginner readers? Does knowledge of letter names hinder students from learning letter sounds?”

"Cee is for cookie, that’s good enough for me…cookie cookie cookie starts with Cee."

—Cookie Monster

Teachers with classroom experience—as well as reading researchers—know that letter names confuse some kids. These children internalize the names of the letters and have a hard time transitioning to letter sounds. For example, some students have a hard time learning that the letter "c" can represent the sound /k/ as in “cat” because they are stuck on the sound /see/.

Other students might say /d/ for the letter "w" (double-you), or /w/ for the letter "y" (why).

(For further sources, and for a detailed study on the effects of letter names on childrens’ spelling, see Instruction matters: spelling of vowels by children in England and the US by Rebecca Treiman, 2012).

Now imagine you are a 5 years old student, and your kindergarten teacher offers you the following explanation:

Here is a new letter (E). The name of this letter is E. The letter E makes the sound /eh/. But the letter E can make another sound: /ee/. Did you notice that the sound /ee/ is also the name of the letter E? That's because sometimes the letter E says its name: /ee/.

Now the sound /eh/ is a short E. The sound /ee/ is a long E. So when the letter E makes a long sound, it says /ee/, but when the letter E makes a short sound, it says /eh/.

Repeat after me: "The letter E makes two sounds. The short E sound is /eh/, and the long E sound is /ee/.

This explanation might make sense to adults, but can be very confusing to first-time readers.

So how many students suffer from letter-name confusion? Is it the majority or just a handful of students?

We acknowledge that a minority of students will be confused by letter names; still, we were compelled to exclude letter names from our phonics curriculum for two reasons.

Reason 1: Helping Teachers Become Expert Phonics Instructors

Many KG and first-grade teachers enter the classroom without sufficient training in phonics. These dedicated teachers do not realize that they can sow confusion with the following instructions: "This is the letter /ay/. We use the letter /ay/ at the beginning of the word "apple." Repeat after me: /ay/, /ay/, /apple/." Imagine how confusing this could be for a five-year-old child.

We created CAPIT to both teach children to read and to help teachers become expert phonics instructors. Teachers who use CAPIT will not make these kinds of category errors, i.e., mixing letter names and letter sounds, when communicating with students.

Reason 2: Equity

We recognize that most students will not suffer from letter name confusion, but the reality that some students will be confused compelled us to exclude letter names. In the name of equity and fairness, we decided to create a program that leaves no students behind.

Our Solution: Visual Mnemonics

Letter name advocates point to research that indicates that letter names facilitate the learning of letter sounds. This letter sound learning is caused by the fact that many letters begin with the letter's sound (Knowing letter names and learning letter sounds: A causal connection, David L. Share (2004)). One wonders: would children be better off if we collectively changed the following letter names?

F: from /ef/ to /fee/

H: from /aitch/ to /hee/

L: from /el/ to /lee/

M: from /em/ to /mee/

N: from /en/ to /nee/

Qu: from /cue/ to /quee/

R: from /ar/ to /ree/

S: from /es/ to /see/

W: from /double-u/ to /wee/

Y: from /why/ to /yee/

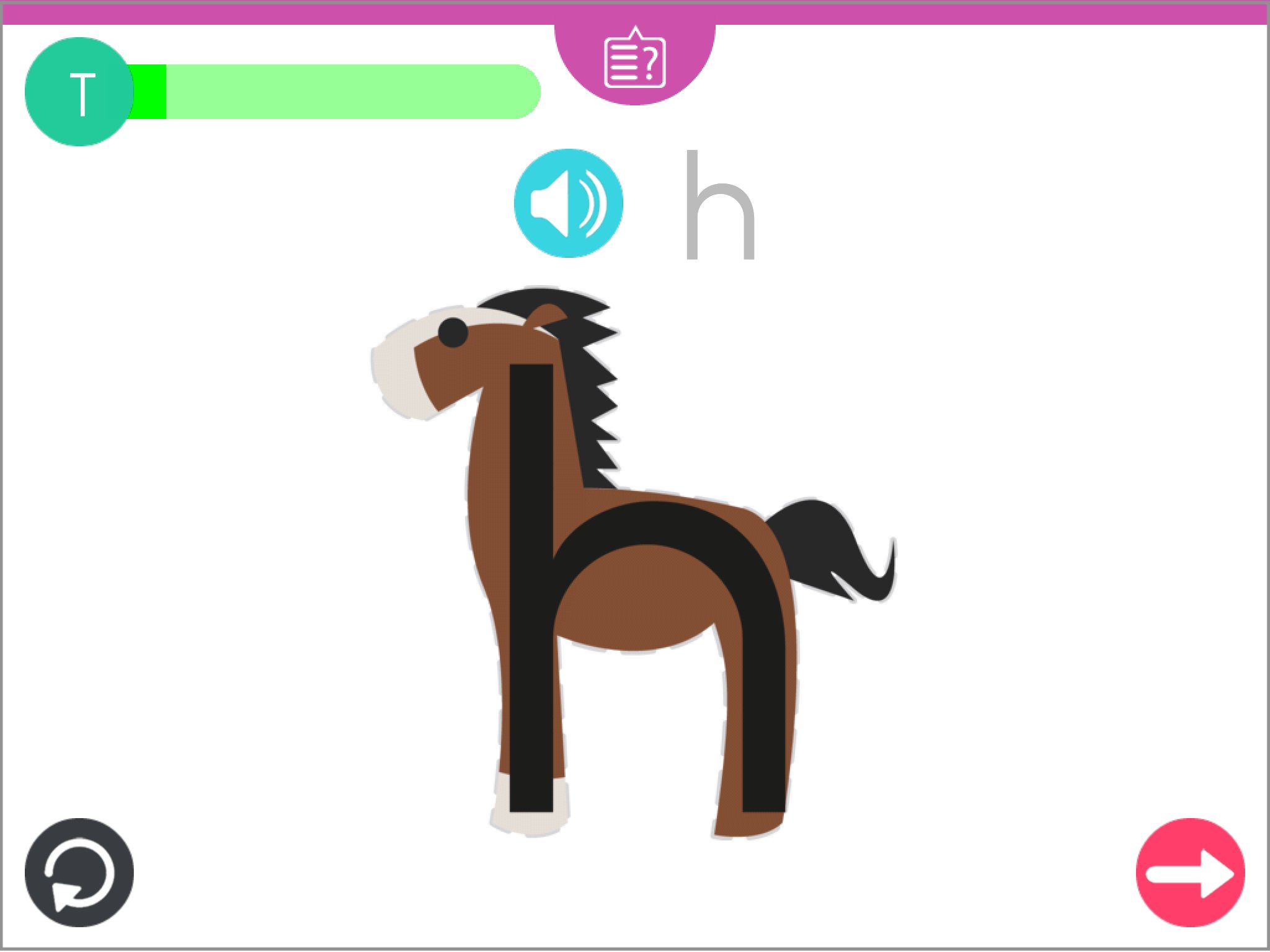

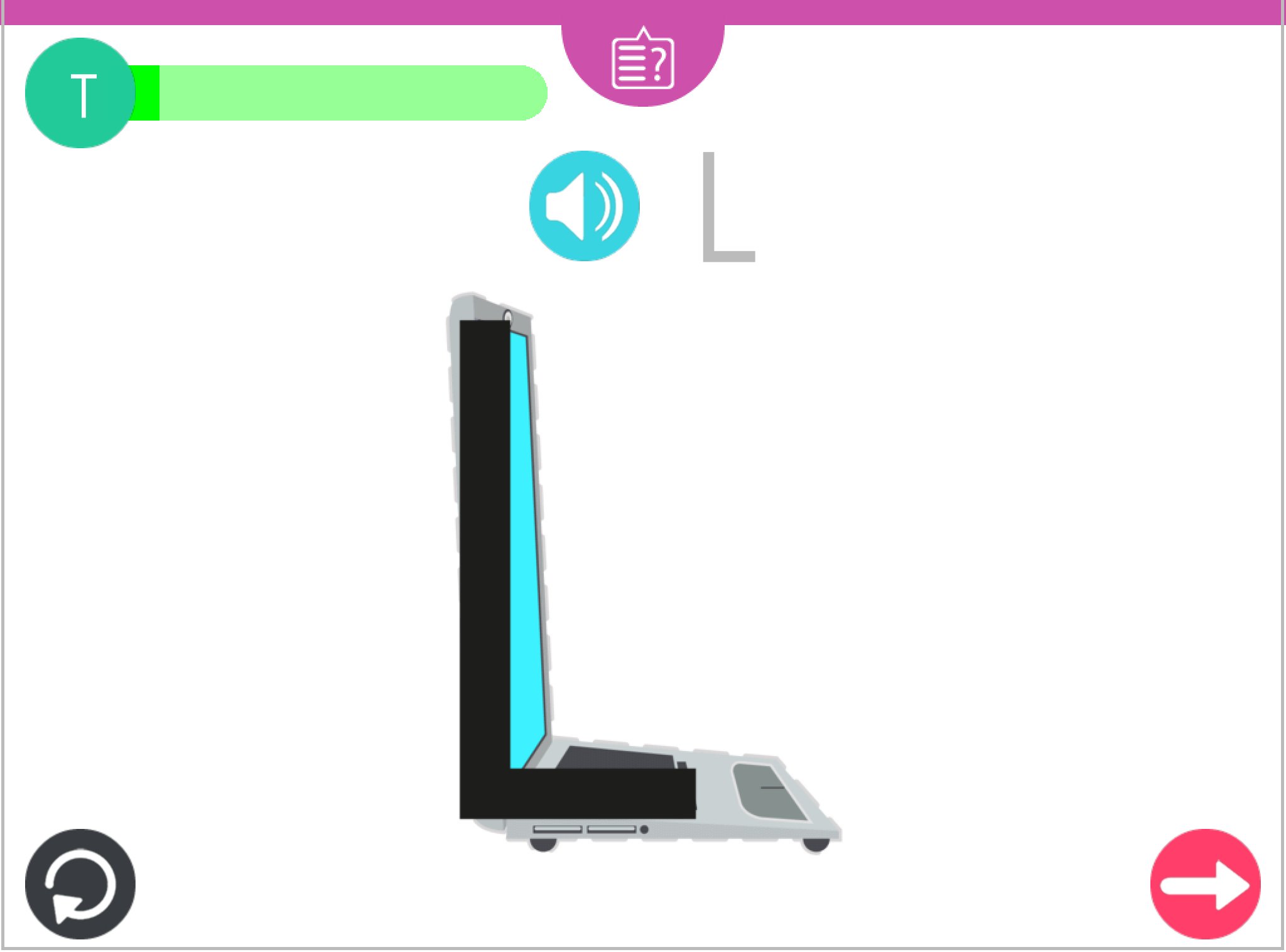

We do not seriously suggest that we ought to implement this change. We did something even better: we created Visual Mnemonics that confer all the benefits of letter names—an object with a proper name that begins with each letter's corresponding phoneme. For example:

F: as in /Flag/

h: as in /horse/

L: as in /Laptop/

With our unique visual mnemonics, 5-year-old kindergarten students master letter sounds in just three months, after which they begin blending CVC words. To learn more about our unique visual mnemonics, CLICK HERE.

Conclusion

We encourage teachers to teach letter names to their students. But we highly recommend that this happens outside of and in addition to their phonics instruction.